The Challenger Deep is one of the most extreme environments on Earth and one that few scientists have ever been able to reach because of pressure so intense that it can easily crush conventional oceanographic equipment.

Now, a researcher at Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S., has joined that coterie after successfully deploying an autonomous lander from the area in the southern tip of the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific.

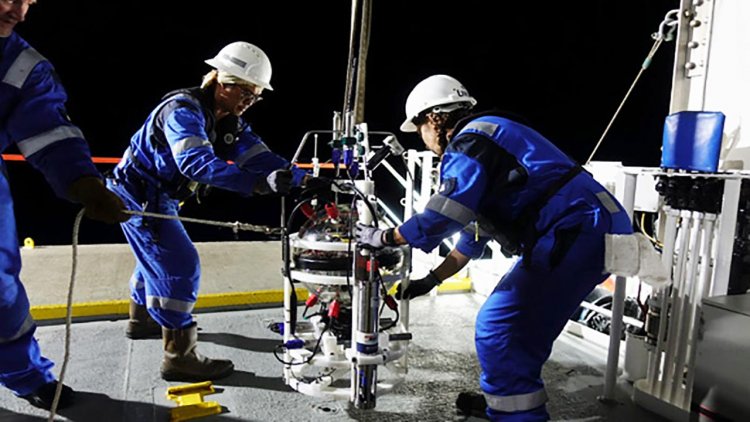

David Barclay, an associate professor in the Department of Oceanography and Canada Research Chair, led a team on board DSSV Pressure Drop that dropped his home-grown Deep Acoustic Lander—aptly named DAL—to the bottom of the trench last Friday.

Dr. Barclay said:

“The achievement of sending something down there, having it survive that pressure, getting it back to the surface and recovering it is a big technological and engineering win.

The demonstration of technology proves that we now have an elevator to the deep. The potential to develop more measurement capability for other researchers is huge. We could make measurements of ocean chemistry, biology, geology and physics at any depth.”

The lander is an autonomous free-falling instrument developed at Dalhousie that records four channels of audio and the surrounding water properties. Dr. Barclay used an array of four hydrophones to capture the ambient sound in the trench. The array, like our ears, allows us to separate different sources of sound and determine exactly how they mix with frequency and depth.

A recording captures the sounds of the DAL deployment from when it plunges into the ocean—picking up a mixture of the ship’s whirring propellers, distant waves, storms, ships and rainfall—to when it releases its anchor and rises to the surface.

Even at 3,000 meters below, it can pick up the sound of a bulk carrier passing dozens of kilometers away. The sound of glass shards breaking off the DAL’s sphere under the environment’s enormous pressure can also be heard. It becomes silent, however, after the lander plunks down on the bottom in one of the quietest places in the world’s oceans—making it only the second recording from the bottom of the Challenger Deep.

The acoustic and oceanographic data collected on the mission will provide valuable insight into the fundamental properties of seawater at high pressures while also informing a depth-dependent noise model of the deep ocean. That can quantify and shed light on the human impact on the underwater sound field, while also helping design systems that can better cut through the noise to find sound-producing objects in the ocean, such as whales, ships and submarines.