Researchers find new transport route for carbonaceous material from productive Arctic marginal seas to the deep sea

Every year, the cross-shelf transport of carbon-rich particles from the Barents and Kara Seas could bind up to 3.6 million metric tons of CO2 in the Arctic deep sea for millennia.

In this region alone, a previously unknown transport route uses the biological carbon pump and ocean currents to absorb atmospheric CO2 on the scale of Iceland’s total annual emissions, as researchers from the Alfred Wegener Institute and partner institutes report in the current issue of the journal Nature Geoscience.

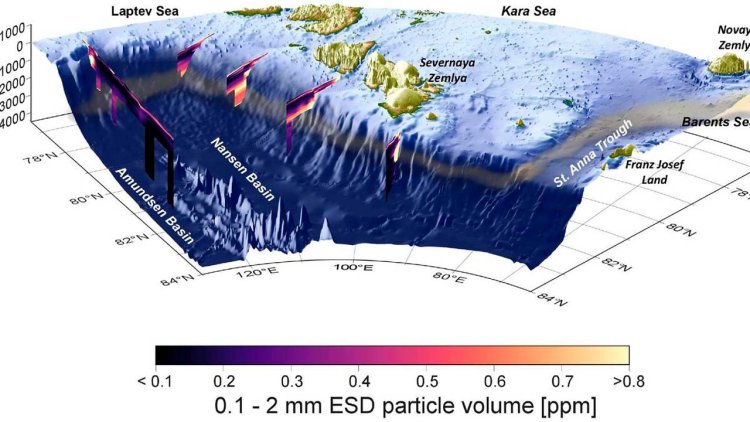

Compared to other oceans, the biological productivity of the central Arctic Ocean is limited, since sunlight is often in short supply – either due to the Polar Night or to sea-ice cover – and the available nutrient sources are scarce. Consequently, microalgae (phytoplankton) in the upper water layers have access to less energy than their counterparts in other waters. As such, the surprise was great when, on the expedition ARCTIC2018 in August and September 2018 on board the Russian research vessel Akademik Tryoshnikov, large quantities of particulate – i.e., stored in plant remains – carbon were discovered in the Nansen Basin of the central Arctic. Subsequent analyses revealed a body of water with large amounts of particulate carbon to depths of up to two kilometres, composed of bottom water from the Barents Sea. The latter is produced when sea ice forms in winter, then cold and heavy water sinks, and subsequently flows from the shallow coastal shelf down the continental slope and into the deep Artic Basin.

“Based on our measurements, we calculated that through this water-mass transport, more than 2,000 metric tons of carbon flow into the Arctic deep sea per day, the equivalent of 8,500 metric tons of atmospheric CO2. Extrapolated to the total annual amount revealed even 13.6 million metric tons of CO2, which is on the same scale as Iceland’s total annual emissions,” explains Dr Andreas Rogge, first author of the Nature Geoscience study and an oceanographer at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI).

This plume of carbon-rich water spans from the Barents- and Kara Sea shelf to roughly 1,000 kilometres into the Arctic Basin. In light of this newly discovered mechanism, the Barents Sea – already known to be the most productive marginal sea in the Arctic – would appear to effectively remove roughly 30 percent more carbon from the atmosphere than previously believed. Moreover, model-based simulations determined that the outflow manifests in seasonal pulses, since in the Arctic’s coastal seas, the absorption of CO2 by phytoplankton only takes place in summer.

Understanding transport and transformation processes within the carbon cycle is essential to creating global carbon dioxide budgets and therefore also projections for global warming. On the ocean’s surface, single-celled algae absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and sink towards the deep sea when aged out. Once carbon bound in this manner reaches the deep water, it stays there until overturning currents bring the water back to the ocean’s surface, which takes several thousand years in the Arctic. And if the carbon is deposited in deep-sea sediments, it can even be trapped there for millions of years, as only volcanic activity can release it. This process, also known as the biological carbon pump, can remove carbon from the atmosphere for long periods of time and represents a vital sink in our planet’s carbon cycle. The process also represents a food source for the local deep sea fauna like sea stars, sponges and worms. What percentage of the carbon is actually absorbed by the ecosystem is something only further research can tell us.

The polar shelf seas harbour other largely unexplored regions in which bottom water is formed and flows into the deep sea. As such, it can be assumed that the global influence of this mechanism as a carbon sink is actually much greater.

“However, due to the ongoing global warming, less ice and therefore less bottom water is formed. At the same time more light and nutrients are available for the phytoplankton, allowing more CO2 to be bound. Accordingly, it’s currently impossible to predict how this carbon sink will develop, and the identification of potential tipping points urgently calls for additional research,” says Andreas Rogge.