NOAA Fisheries is leading a major effort to evaluate how next-generation ocean gliders can transform ocean monitoring and marine mammal conservation, while also benefitting U.S. fishermen and ocean industries.

How can underwater gliders transform the way we study the ocean?

NOAA Fisheries scientists are eager to explore this question during a unique glider challenge in Hawaiʻi this month.

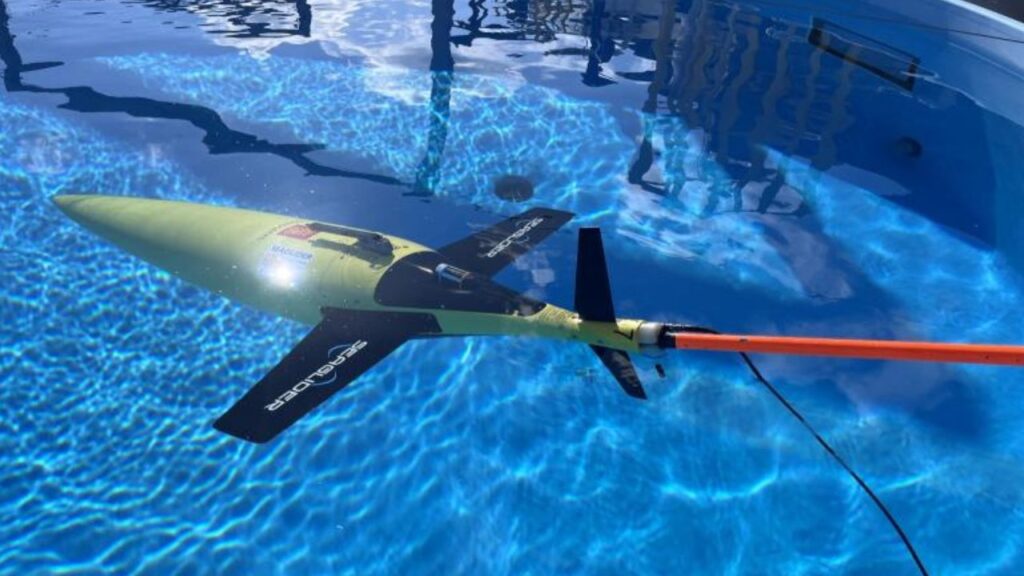

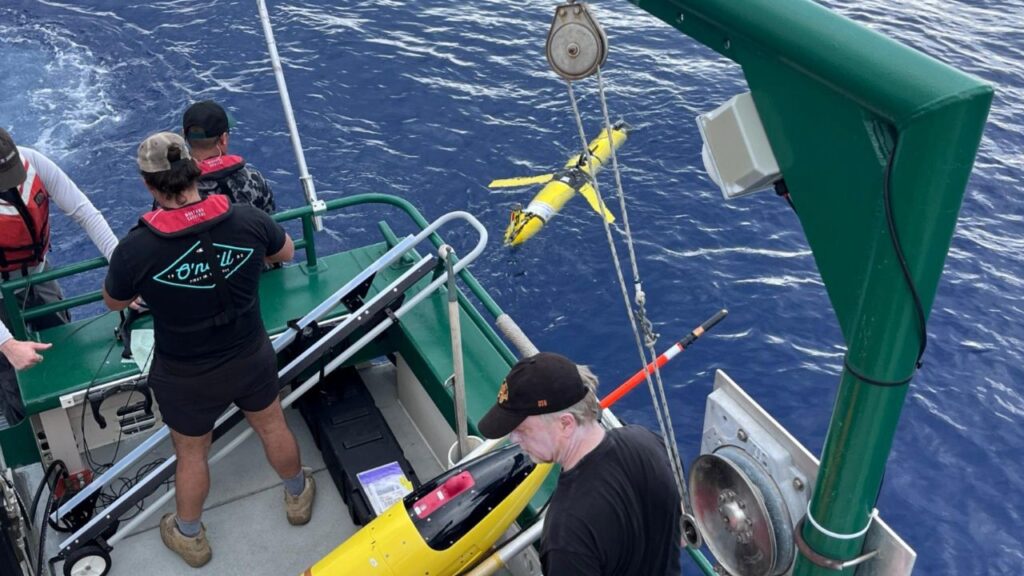

They are leading a rigorous assessment of gliders equipped with passive acoustic sensors to record underwater sounds.

The gliders, and their pilots, will complete a series of missions to demonstrate their capabilities in studying marine mammals and their ecosystems.

Industry and academic partners joining the 2-week challenge include:

- Cornell University

- Oregon State University

- ALSEAMAR

- Hefring Engineering

- JASCO

- Teledyne Marine

“It’s a really important event for us,” said Erin Oleson, Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center Protected Species Division director. “By advancing the use of innovative and cost-effective uncrewed vessels, like gliders, we can more precisely support marine species and ecosystems, which in turn supports a strong and sustainable ocean economy.”

For decades, we have conducted ship-based surveys for large-scale monitoring of whales, dolphins, and porpoises. The data allows to estimate population size, location, and trends to support conservation and sustainable fisheries.

These ship-based surveys are considered the “gold standard” for monitoring marine mammals. They provide critical data through visual observations, acoustic recordings, tissue sampling, and satellite tagging.

However, ship-based surveys have limitations. They require extensive planning and can be costly and resource intensive, so they typically occur every few years. That means teams may not get a precise count of whales and dolphins that move through the region outside of the survey periods, leaving critical gaps in understanding.

Passive acoustic-equipped gliders offer a powerful complement to shipboard surveys—filling data gaps and expanding coverage opportunities.

“We know that passive acoustic monitoring is a really exceptional, proven method for detecting marine mammals underwater,” Oleson said. “Gliders give us a way to move passive acoustic monitoring technology around the ocean in a way that replicates and enhances our ship surveys. It’s exciting.”

In contrast to the ship-based surveys, gliders offer rapidly advancing capabilities and a cost-effective way to survey more frequently and across more areas. This additional glider data would help ensure federal protections are right-sized for marine mammals and sustainable fisheries.

Gliders also offer the potential to support real-time responses in the future—like locating a dolphin pod scientists need to tag, or alerting fishermen to whales near a fishing spot.

No single glider is the best at everything. One underwater glider system might excel at gathering data across a large area, while another may be quieter and better able to listen for whales and dolphins.

“We need to know what the gliders can do well, and where they might be limited.” Shannon Rankin, passive acoustic ecologist with the Southwest Fisheries Science Center. “These insights will help us determine the best way to collect data for various management needs.”

This Hawaiʻi glider challenge, while based in the Pacific, is part of a larger effort with broader implications.

The findings will help NOAA, academia, and industry accelerate glider development and use in marine mammal and ecosystems research nationwide.

“Our goal is to transition to using passive acoustic gliders to augment our shipboard surveys to better support our management needs,” Rankin said. By identifying the strengths of each underwater glider system, scientists aim to operationalize technologies that are best suited for monitoring whales, dolphins, and the ecosystems on which they—and we—depend.

This is just the start of how these tools can be used, Oleson added.

These gliders, with a variety of data collection packages, could be used beyond marine mammal monitoring. They could help us track fish spawning and distribution, predict red tides or algal blooms, measure marine food web changes, and more. They will be foundational tools for the future of NOAA Fisheries surveys.